$600,000 verdict against Ports Authority upheld

Staff Report //September 23, 2021//

The S.C. Court of Appeals has unanimously affirmed a $600,000 award to a trucker injured by a S.C. Ports Authority crane operator, finding no evidence that the trucker breached a duty of care in an incident that left him with neck and back injuries.

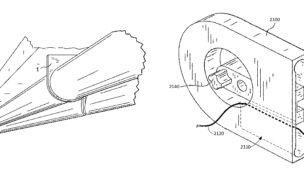

Curtis Mills was offloading a cargo container on the Port Authority’s Wando Terminal in 2012, when he contends that the crane operator lifted and shook the container while it was still attached to the truck, separating them and dropping the truck several feet to the ground. Mills said that the crane operator left the scene after ignoring his attempts to flag him down.

The Ports Authority argued that a Charleston County jury’s verdict in Mills’ favor in 2018 shouldn’t stand because the trial court refused to charge comparative negligence and denied its motion for either a new trial absolute or a new trial nisi remittitur, and the award—reduced to the $300,000 statutory cap for damages against a government entity under the state’s Tort Claims Act—was excessive.

But in a Sept. 15 opinion, Chief Judge James Lockemy wrote that the Ports Authority had failed to present evidence supporting an inference of Mill's negligence.

“The trial court is required to charge only principles of law that apply to the issues raised in the pleadings and developed by the evidence in support of those issues,” Lockemy wrote, citing the state Supreme Court’s 2000 ruling in Clark v. Cantrell.

Mills had asserted that the crane operator noticed that the container was still attached to the chassis and truck but failed to alert him and safely lower the container and truck.

At trial, Mills testified that he had removed all four of the locking mechanisms, known as “pins,” on the shipping container when he checked in at the terminal’s gate and that nothing requires him to inspect the pins both at the gate and prior to the lift. Ports Authority employees confirmed that Mills removed the pins at the gate but said that they sometimes work their way back into place on the drive from the gate to the crane row.

The Ports Authority unsuccessfully moved for a directed verdict and then sought a comparative negligence charge, arguing that drivers are responsible for ensuring that all pins are disengaged, but Charleston County Circuit Court Judge Kristi Lea Harrington declined to make that charge.

In affirming the verdict and award, the appeals court found that while the crane operator’s testimony provided some evidence that Mills was partially at fault because he tried to free the truck by driving it forward while it was attached to the crane, the Ports Authority failed to argue the conflicting testimony regarding the cause of the incident or offer evidence of Mills’ potential fault. It argued only, the court found, that drivers are responsible for ensuring that containers are unhooked, at the gate and time of the lift.

“Because the Ports Authority did not raise this argument to the trial court in support of its request for a comparative negligence charge, we cannot conclude the trial court erred by declining to charge comparative negligence on this basis,” Lockemy wrote.

The court also rejected the Ports Authority’s argument that the trial court erred in refusing to grant a new trial absolute or a new trial nisi remittitur because the jury’s verdict was excessive and not supported by the evidence, noting the deference given to trial courts, which are more familiar with the evidentiary atmosphere and have a better-informed view of the damages.

“A new trial absolute should be granted only if the verdict is so grossly excessive that it shocks the conscience of the court and clearly indicates the amount of the verdict was the result of caprice, passion, prejudice, partiality, corruption or other improper motive,” Lockemy wrote, quoting Knoke v. S.C. Department of Parks, Recreation & Tourism, decided by the state’s Supreme Court in 1996.

The court has the power to reduce the verdict by granting a new trial nisi remittitur where it finds the verdict “merely excessive,” but found here evidence supporting the jury’s verdict and award.

Randell Stoney and John Fletcher of Barnwell Whaley Patterson & Helms and Randolph Lowell of Willoughby & Hoefer, both in Charleston, represented the Ports Authority. None of the attorneys immediately responded to a request for comment.

Mills was represented by Ladson Howell Jr. of Mount Pleasant, who said that he is “cautiously optimistic” that the decision will make the port a safer place.

“But I do not have any firsthand knowledge about whether the port has changed its policies with regard to ascertaining that safety pins have not jostled back into place or any additional safeguards to ensure that trucks don’t get lifted off the ground,” Howell said.

The 12-page decision is Mills v. South Carolina Ports Authority (Lawyers Weekly No. 011-079-21).